Happy Birthday, Eleanor Audley!

The epitaph on the headstone adorning the final resting place of actress Eleanor Audley reads: “A Kind Friend to All.” And while it’s undeniably true that Audley—born Eleanor Zellman on this date in NYC in 1905—was held in the highest regard by her thespic peers, it’s a marked contrast from the roles for which fans remember her today. Eleanor not only provided the voices for two of the most menacing villainesses in Walt Disney animation history, she could be heard as spirit medium “Madame Leota Toombs” (a disembodied head inside a crystal ball) at the “Haunted Mansion” attractions at both Disneyland and Walt Disney World.

A small role in the Broadway hit Howdy, King (1926) launched the acting career of a 20-year-old Eleanor. She followed up this debut with performances in such productions as On Call (1928), Pigeons and People (1933), Thunder on the Left (1933), Kill That Story (1934), Ladies’ Money (1934), and Susan and God (1937). Like many of her fellow actors, Audley found work enough to sustain her in radio—lending her talents to daytime dramas like By Kathleen Norris. A blurb in an Evans Plummer column from a 1935 issue of Radio Life gives Eleanor an “atta girl”: “Plums to Eleanor Audley, of the Windy City cast of Three Men on a Horse, who without rehearsal and but thirty minutes’ notice came to the rescue of the Monday night Princess Pat drama when actress Dorothy Mallinson was seized with an acute attack of asthma caused from eating strawberry shortcake.”

A small role in the Broadway hit Howdy, King (1926) launched the acting career of a 20-year-old Eleanor. She followed up this debut with performances in such productions as On Call (1928), Pigeons and People (1933), Thunder on the Left (1933), Kill That Story (1934), Ladies’ Money (1934), and Susan and God (1937). Like many of her fellow actors, Audley found work enough to sustain her in radio—lending her talents to daytime dramas like By Kathleen Norris. A blurb in an Evans Plummer column from a 1935 issue of Radio Life gives Eleanor an “atta girl”: “Plums to Eleanor Audley, of the Windy City cast of Three Men on a Horse, who without rehearsal and but thirty minutes’ notice came to the rescue of the Monday night Princess Pat drama when actress Dorothy Mallinson was seized with an acute attack of asthma caused from eating strawberry shortcake.”

By the 1940s, Eleanor Audley continued to demonstrate what a trouper she could be in the aural medium with appearances on such shows as Adventure Ahead, The Big Story, The Bishop and the Gargoyle, Ellery Queen, Encore Theatre, Escape, The Eternal Light, The Haunting Hour, Lawyer Q, The Lux Radio Theatre, My Home Town, The NBC University Theatre, Pursuit, The Railroad Hour, Richard Diamond, Private Detective, Romance, The Sealtest Variety Theatre, Suspense, This is Your FBI, The Weird Circle, The Whistler, and Words at War. Audley had a recurring role on the Lucille Ball-Richard Denning sitcom My Favorite Husband as Leticia Cooper (Lucy’s character’s mother-in-law) and on The Story of Dr. Kildare she played Molly Byrd, the receptionist at Blair General Hospital. Her busiest radio role was probably on Father Knows Best; Eleanor was Elizabeth Smith, the next-door neighbor of the Family Anderson (Herb Vigran was her husband Hector and Sam Edwards their son Billy).

By the 1940s, Eleanor Audley continued to demonstrate what a trouper she could be in the aural medium with appearances on such shows as Adventure Ahead, The Big Story, The Bishop and the Gargoyle, Ellery Queen, Encore Theatre, Escape, The Eternal Light, The Haunting Hour, Lawyer Q, The Lux Radio Theatre, My Home Town, The NBC University Theatre, Pursuit, The Railroad Hour, Richard Diamond, Private Detective, Romance, The Sealtest Variety Theatre, Suspense, This is Your FBI, The Weird Circle, The Whistler, and Words at War. Audley had a recurring role on the Lucille Ball-Richard Denning sitcom My Favorite Husband as Leticia Cooper (Lucy’s character’s mother-in-law) and on The Story of Dr. Kildare she played Molly Byrd, the receptionist at Blair General Hospital. Her busiest radio role was probably on Father Knows Best; Eleanor was Elizabeth Smith, the next-door neighbor of the Family Anderson (Herb Vigran was her husband Hector and Sam Edwards their son Billy).

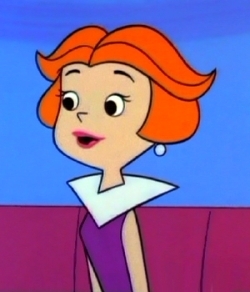

Eleanor Audley’s motion picture debut was an uncredited role in 1949’s The Story of Molly X—a “women’s prison” picture that features many old-time radio veterans: Cathy Lewis, Sara Berner, Sandra Gould, Elliott Lewis, Wally Maher, and Hal March, just to name a few. Eleanor’s second film, however, would prove to be one of her most memorable: she provided the voice of Lady Tremaine, the “wicked stepmother” in the Disney animation classic Cinderella (1950). Not only did Audley provide the tones of the woman who made the titular heroine’s life quite unpleasant, but animators modeled the character on the actress’ physical appearance. Eleanor would reprise the wicked stepmother role on a February 15, 1951 broadcast of radio’s Hallmark Playhouse, “The Story of Cinderella,” and tackled a similar showcase in a memorable outing of The Six Shooter (“When the Shoe Doesn’t Fit,” 06/17/54) that found protagonist Britt Ponset in a Cinderella-inspired tale.

Eleanor Audley’s motion picture debut was an uncredited role in 1949’s The Story of Molly X—a “women’s prison” picture that features many old-time radio veterans: Cathy Lewis, Sara Berner, Sandra Gould, Elliott Lewis, Wally Maher, and Hal March, just to name a few. Eleanor’s second film, however, would prove to be one of her most memorable: she provided the voice of Lady Tremaine, the “wicked stepmother” in the Disney animation classic Cinderella (1950). Not only did Audley provide the tones of the woman who made the titular heroine’s life quite unpleasant, but animators modeled the character on the actress’ physical appearance. Eleanor would reprise the wicked stepmother role on a February 15, 1951 broadcast of radio’s Hallmark Playhouse, “The Story of Cinderella,” and tackled a similar showcase in a memorable outing of The Six Shooter (“When the Shoe Doesn’t Fit,” 06/17/54) that found protagonist Britt Ponset in a Cinderella-inspired tale.

Eleanor Audley’s cinematic oeuvre also includes credited and uncredited parts in classics like No Way Out (1950), Three Secrets (1950), Pretty Baby (1950), With a Song in My Heart (1952), Prince of Players (1955), Untamed (1955), Cell 2455, Death Row (1955), All That Heaven Allows (1955), The Unguarded Moment (1956), Full of Life (1956), Home Before Dark (1958), and The Second Time Around (1961). Eleanor returned to her radio roots for her most famous movie showcase, however: voicing the evil fairy known as Maleficent in another animated feature from Walt Disney, 1959’s Sleeping Beauty. At the time production was underway, Audley initially turned down the assignment because she was battling tuberculosis…but she eventually rose to the occasion, and as she had done on Cinderella allowed Beauty’s animators to borrow some of her own physical features for the animated baddie. (That unforgettable diabolical cackle of Maleficent’s, though—that was all Eleanor.) When Sleeping Beauty was finished, Audley was treated to a special private screening of the film.

Eleanor Audley’s cinematic oeuvre also includes credited and uncredited parts in classics like No Way Out (1950), Three Secrets (1950), Pretty Baby (1950), With a Song in My Heart (1952), Prince of Players (1955), Untamed (1955), Cell 2455, Death Row (1955), All That Heaven Allows (1955), The Unguarded Moment (1956), Full of Life (1956), Home Before Dark (1958), and The Second Time Around (1961). Eleanor returned to her radio roots for her most famous movie showcase, however: voicing the evil fairy known as Maleficent in another animated feature from Walt Disney, 1959’s Sleeping Beauty. At the time production was underway, Audley initially turned down the assignment because she was battling tuberculosis…but she eventually rose to the occasion, and as she had done on Cinderella allowed Beauty’s animators to borrow some of her own physical features for the animated baddie. (That unforgettable diabolical cackle of Maleficent’s, though—that was all Eleanor.) When Sleeping Beauty was finished, Audley was treated to a special private screening of the film.

Eleanor Audley continued to perform in front of a radio microphone throughout the 1950s with appearances on programs like The Adventures of the Saint, Family Theatre, Fibber McGee & Molly, The Halls of Ivy, Hollywood Star Playhouse, The Life of Riley, Night Beat, and Screen Directors’ Playhouse. Even as radio was waiting for the hook that would yank it off the national stage, Audley could be found performing on the likes of The CBS Radio Workshop and Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar. But as assignments in the aural medium started to become scarcer and scarcer, Eleanor would eventually make the transition to the small screen, guest starring on everything from I Love Lucy to The Twilight Zone. She had recurring roles on series like The Swamp Fox (a Disneyland serial), The Gale Storm Show, The Joey Bishop Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Beverly Hillbillies, Mister Ed, Pistols ‘n’ Petticoats, and My Three Sons. Couch potatoes probably know her best as Eunice Douglas—the snobbish mother of Oliver Wendell Douglas (Eddie Albert) on the beloved sitcom Green Acres. Unlike most mother-in-law stereotypes, Eunice actually got along better with her daughter-in-law (Eva Gabor as Lisa) than her own son! Audley had hoped to reprise her Eunice role in the reunion TV movie Return to Green Acres (1990), but illness put the kibosh on that; she passed away in 1991 at the age of 86.

Eleanor Audley continued to perform in front of a radio microphone throughout the 1950s with appearances on programs like The Adventures of the Saint, Family Theatre, Fibber McGee & Molly, The Halls of Ivy, Hollywood Star Playhouse, The Life of Riley, Night Beat, and Screen Directors’ Playhouse. Even as radio was waiting for the hook that would yank it off the national stage, Audley could be found performing on the likes of The CBS Radio Workshop and Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar. But as assignments in the aural medium started to become scarcer and scarcer, Eleanor would eventually make the transition to the small screen, guest starring on everything from I Love Lucy to The Twilight Zone. She had recurring roles on series like The Swamp Fox (a Disneyland serial), The Gale Storm Show, The Joey Bishop Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show, The Beverly Hillbillies, Mister Ed, Pistols ‘n’ Petticoats, and My Three Sons. Couch potatoes probably know her best as Eunice Douglas—the snobbish mother of Oliver Wendell Douglas (Eddie Albert) on the beloved sitcom Green Acres. Unlike most mother-in-law stereotypes, Eunice actually got along better with her daughter-in-law (Eva Gabor as Lisa) than her own son! Audley had hoped to reprise her Eunice role in the reunion TV movie Return to Green Acres (1990), but illness put the kibosh on that; she passed away in 1991 at the age of 86.

That “Cinderella” episode of The Six Shooter that I mentioned earlier in this essay? Well, it’s available on the Radio Spirits release Six Shooter: Special Edition, and you’ll also find our birthday girl on another Shooter collection, Gray Steel. We also feature Eleanor Audley on three of her signature series: The Story of Dr. Kildare, Father Knows Best (on Great Radio Christmas), and My Favorite Husband (Great Radio Sitcoms). There’s a wealth of Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar sets with work by Eleanor—Fabulous Freelance, Fatal Matters, and Murder Matters—and on Jack Benny: Be Our Guest, Ms. Audley is among the cast of The Hotpoint Holiday Hour presentation of “The Man Who Came to Dinner” (12/25/49). Hey—you’ve still got room in your shopping cart for The Big Story: As It Happened and The Weird Circle: Toll the Bell. Happy birthday to one of our very favorite character actresses!

That “Cinderella” episode of The Six Shooter that I mentioned earlier in this essay? Well, it’s available on the Radio Spirits release Six Shooter: Special Edition, and you’ll also find our birthday girl on another Shooter collection, Gray Steel. We also feature Eleanor Audley on three of her signature series: The Story of Dr. Kildare, Father Knows Best (on Great Radio Christmas), and My Favorite Husband (Great Radio Sitcoms). There’s a wealth of Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar sets with work by Eleanor—Fabulous Freelance, Fatal Matters, and Murder Matters—and on Jack Benny: Be Our Guest, Ms. Audley is among the cast of The Hotpoint Holiday Hour presentation of “The Man Who Came to Dinner” (12/25/49). Hey—you’ve still got room in your shopping cart for The Big Story: As It Happened and The Weird Circle: Toll the Bell. Happy birthday to one of our very favorite character actresses!