“…the stars’ own theatre…”

The glamour of the motion picture industry often disguised an uncomfortable truth—that it was an enterprise that rarely had any further use for those movie colony individuals who had fallen on hard times. To lend a helping hand to their former colleagues, luminaries like Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D.W. Griffith banded together in 1921 to create the Motion Picture Relief Fund (MPRF—now known as the MPTF, to incorporate television). Joseph M. Schenck served as the first president, with Pickford as vice-president and a board of trustees that included Fairbanks, Cecil B. DeMille, Harold Lloyd, and Hal Roach.

The advent of talkies really required the MPRF to step up their game, as many individuals were now unemployed due to the changes (especially performers whose voices simply couldn’t conform to the standards of the new medium). Appeals for donations to the fund would be the focus of various charity balls, motion picture premieres, fashion shows and the like. Mary Pickford, to meet the increasing demand for assistance, instituted the Payroll Pledge Program—a plan whereby deductions from anyone making over $200 a week would be automatic, with studio workers pledging one-half of one percent of their earnings. Six years later, participation in the PPP would expand to include talent groups, unions, and producer representatives.

The advent of talkies really required the MPRF to step up their game, as many individuals were now unemployed due to the changes (especially performers whose voices simply couldn’t conform to the standards of the new medium). Appeals for donations to the fund would be the focus of various charity balls, motion picture premieres, fashion shows and the like. Mary Pickford, to meet the increasing demand for assistance, instituted the Payroll Pledge Program—a plan whereby deductions from anyone making over $200 a week would be automatic, with studio workers pledging one-half of one percent of their earnings. Six years later, participation in the PPP would expand to include talent groups, unions, and producer representatives.

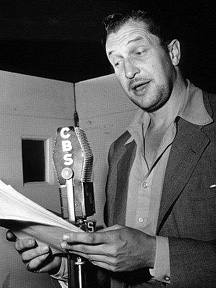

The Screen Actors Guild sought to improve this donation effort by requiring compulsory contributions from its “Class A” members. Jean Hersholt, president at that time, was determined to raise more money for the MPRF (he wanted to expand the Fund to include covering the costs for medical care). He suggested, along with Music Corporation of America (MCA) founder Dr. Jules C. Stein, the creation of a radio program where major stars would appear, donating their salaries to the MPRF. With members of both the Directors and Writers guilds agreeing to also contribute their services for free, the result was The Screen Guild Theatre—which premiered over 61 CBS radio stations on this date in 1939.

The Screen Actors Guild sought to improve this donation effort by requiring compulsory contributions from its “Class A” members. Jean Hersholt, president at that time, was determined to raise more money for the MPRF (he wanted to expand the Fund to include covering the costs for medical care). He suggested, along with Music Corporation of America (MCA) founder Dr. Jules C. Stein, the creation of a radio program where major stars would appear, donating their salaries to the MPRF. With members of both the Directors and Writers guilds agreeing to also contribute their services for free, the result was The Screen Guild Theatre—which premiered over 61 CBS radio stations on this date in 1939.

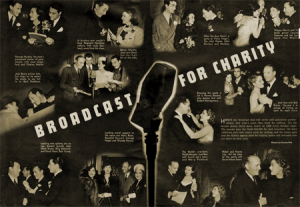

The January 8, 1939 inaugural broadcast of The Gulf Screen Guild Show featured a powerhouse lineup of big-name talent: Judy Garland (who sang Sweet or Hot?), Jack Benny, Joan Crawford, Reginald Gardiner, Ralph Morgan, and George Murphy as master of ceremonies. (Roger Pryor would replace Murph as the show’s host in the fall of 1939 and remained in charge for the remainder of the series’ Gulf Oil run.) Screen Guild started out with a variety format in its early broadcasts before gradually transitioning to adaptations of motion pictures, much in the vein of The Lux Radio Theatre. Lux, however, had an hour for its presentations…The Screen Guild Theatre had half that, which presented a challenge to charitable writers who often had to compress film narratives to fit the tight time frame (22 minutes sans Gulf commercials).

The January 8, 1939 inaugural broadcast of The Gulf Screen Guild Show featured a powerhouse lineup of big-name talent: Judy Garland (who sang Sweet or Hot?), Jack Benny, Joan Crawford, Reginald Gardiner, Ralph Morgan, and George Murphy as master of ceremonies. (Roger Pryor would replace Murph as the show’s host in the fall of 1939 and remained in charge for the remainder of the series’ Gulf Oil run.) Screen Guild started out with a variety format in its early broadcasts before gradually transitioning to adaptations of motion pictures, much in the vein of The Lux Radio Theatre. Lux, however, had an hour for its presentations…The Screen Guild Theatre had half that, which presented a challenge to charitable writers who often had to compress film narratives to fit the tight time frame (22 minutes sans Gulf commercials).

The Gulf Screen Theatre presented a radio adaptation of The Blue Bird (which would be released in 1940) on the December 24, 1939 broadcast with star Shirley Temple (her $35,000 salary was donated to the MPRF). The story goes that, as Shirley launched into her rendition of Someday You’ll Find Your Bluebird, a woman in the audience stood up with a handgun, intending to do America’s favorite movie moppet bodily harm. (She was disarmed, thankfully; purportedly the woman lost a daughter in childbirth on the same day Temple was born and she was convinced that Shirl had stolen her child’s soul.)

The Gulf Screen Theatre presented a radio adaptation of The Blue Bird (which would be released in 1940) on the December 24, 1939 broadcast with star Shirley Temple (her $35,000 salary was donated to the MPRF). The story goes that, as Shirley launched into her rendition of Someday You’ll Find Your Bluebird, a woman in the audience stood up with a handgun, intending to do America’s favorite movie moppet bodily harm. (She was disarmed, thankfully; purportedly the woman lost a daughter in childbirth on the same day Temple was born and she was convinced that Shirl had stolen her child’s soul.)

The Gulf Screen Guild Theatre became an immediate hit — attracting big-name Hollywood celebrities so quickly it looked like Suspense’s waiting room. Promoted in magazine articles as “the only sponsored program on the air which gives all its profits to charity,” the money generated from the show would soon allow Jean Hersholt to purchase (in 1940) the property that would house the future Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital (which opened in 1948). By the summer of 1942, the MPRF had received $800,000 in contributions and, at the end of The Screen Guild Theatre’s 13-year run, the amount in the kitty was a little over $5 million. (Hersholt’s success in establishing the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital, by the way, is the reason why the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award was inaugurated by the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1956—an honorary Oscar given to those individuals “whose humanitarian efforts have brought credit to the industry.”)

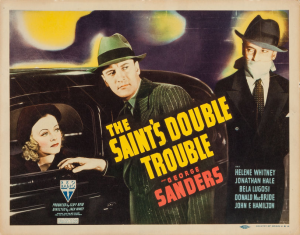

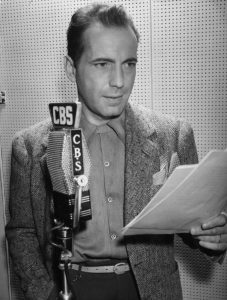

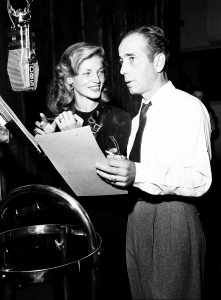

Gulf Oil, the original sponsor of The Screen Guild Theatre, dropped the series in 1942 (uncertainties in the market due to WW2 contributed to this). The Lady Esther cosmetic company start paying the bills in the fall with an all-star broadcast of Yankee Doodle Dandy (featuring James Cagney, Rita Hayworth, and Betty Grable) on October 19, 1942. The Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre continued to be one of radio’s most popular shows, with adaptations of films like Casablanca (with stars Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Paul Heinreid), Theodora Goes Wild (star Irene Dunne and Cary Grant in the Melvyn Douglas role), and a memorable version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs with Edgar Bergen telling the tale to Charlie McCarthy (and Jane Powell as Snow White!). Lady Esther would withdraw sponsorship in 1947 due to a decline in the cosmetics industry, so Camel cigarettes opened up its checkbook for a season on CBS before jumping networks to NBC a year later.

Gulf Oil, the original sponsor of The Screen Guild Theatre, dropped the series in 1942 (uncertainties in the market due to WW2 contributed to this). The Lady Esther cosmetic company start paying the bills in the fall with an all-star broadcast of Yankee Doodle Dandy (featuring James Cagney, Rita Hayworth, and Betty Grable) on October 19, 1942. The Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre continued to be one of radio’s most popular shows, with adaptations of films like Casablanca (with stars Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Paul Heinreid), Theodora Goes Wild (star Irene Dunne and Cary Grant in the Melvyn Douglas role), and a memorable version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs with Edgar Bergen telling the tale to Charlie McCarthy (and Jane Powell as Snow White!). Lady Esther would withdraw sponsorship in 1947 due to a decline in the cosmetics industry, so Camel cigarettes opened up its checkbook for a season on CBS before jumping networks to NBC a year later.

The change in both networks and time slots caused a slide in the ratings for The Screen Guild Theatre. After finishing its run for Camel it moved to ABC in the fall of 1950 (with a September 7 premiere of Twelve O’Clock High and Gregory Peck, Hugh Marlowe, Millard Mitchell, and John Kellogg reprising their film roles) in a now hour-long format. The ABC run ended on May 31, 1951 and the “Screen Guild” appellation was applied to some CBS anthology series (Stars in the Air, Hollywood Sound Stage) before The Screen Guild Theatre returned on March 13, 1952. The show’s final curtain call was on June 29, 1952.

Jack Benny was among the first celebrities to appear on The Screen Guild Theatre and he made a memorable return on an October 20, 1940 broadcast in which he tries to finagle his way into co-starring with Claudette Colbert…despite objections from Basil Rathbone and director Ernst Lubitsch. This premise would appear again on both Jack’s radio and TV programs, and is available on the Radio Spirits collection Jack Benny: Be Our Guest. You can also find Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre adaptations of The Maltese Falcon (from September 20, 1943 with stars Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre) and The Glass Key (July 22, 1946 with Alan Ladd reprising his starring film role) on Smithsonian Legendary Performers: Dashiell Hammett. In addition, Sydney Greenstreet also stars in Screen Guild Theatre’s adaptation of 1944’s The Mask of Dimitrios (from April 16, 1945) on Nero Wolfe: Parties of Death.

Jack Benny was among the first celebrities to appear on The Screen Guild Theatre and he made a memorable return on an October 20, 1940 broadcast in which he tries to finagle his way into co-starring with Claudette Colbert…despite objections from Basil Rathbone and director Ernst Lubitsch. This premise would appear again on both Jack’s radio and TV programs, and is available on the Radio Spirits collection Jack Benny: Be Our Guest. You can also find Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre adaptations of The Maltese Falcon (from September 20, 1943 with stars Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre) and The Glass Key (July 22, 1946 with Alan Ladd reprising his starring film role) on Smithsonian Legendary Performers: Dashiell Hammett. In addition, Sydney Greenstreet also stars in Screen Guild Theatre’s adaptation of 1944’s The Mask of Dimitrios (from April 16, 1945) on Nero Wolfe: Parties of Death.