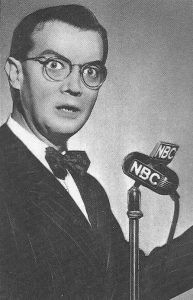

Happy Birthday, Staats Cotsworth!

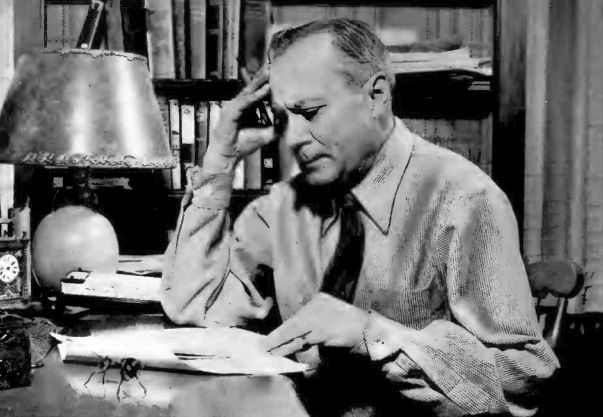

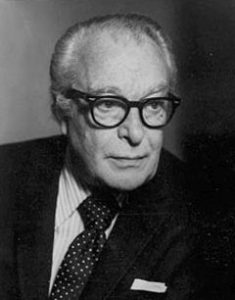

A newspaper man once referred to actor Staats Cotsworth—born in Oak Park, Illinois on this date in 1908—as “the Clark Gable of radio.” It was one of several nicknames Cotsworth would acquire during his long career in the aural medium — the most fitting being “the busiest actor in radio,” because Staats had emoted before a microphone for an estimated 7,500 broadcasts within a 12-year period alone. But Staats could also be labeled a true “Renaissance man.” His acting engagements spanned stage, screen (both silver and small), and radio – but he also pursued other artistic interests, including painting, music, and photography. The latter hobby was a side effect from his most famous role as the “ace cameraman who covers the crime news of the great city” on radio’s Casey, Crime Photographer.

Staats Jennings Cotsworth, Jr. wanted to be a painter since childhood, and to achieve that dream he attended the Pennsylvania Museum’s School of Industrial Art. After receiving his diploma, Staats journeyed to Paris for more instruction at the Académie Colarossi. He returned to the States a few years later where, according to his first wife Muriel Kirkland Cotsworth, he illustrated several books before receiving a commission to paint murals in some Washington bowling alleys. It was only after he returned to New York (it was difficult to sell paintings during the Great Depression) that Cotsworth heard “the roar of the greasepaint and the smell of the crowd” and decided that an actor’s life was for him. He began as a member of Eve LeGalliene’s Civic Repertory Theatre, where he appeared in Alice in Wonderland (as The Mad Hatter) and Hedda Gabler. (Two of Staats’ fellow thespians in this troupe were Burgess Meredith and Parker Fennelly.)

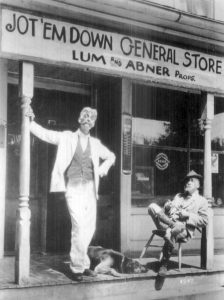

Staats Jennings Cotsworth, Jr. wanted to be a painter since childhood, and to achieve that dream he attended the Pennsylvania Museum’s School of Industrial Art. After receiving his diploma, Staats journeyed to Paris for more instruction at the Académie Colarossi. He returned to the States a few years later where, according to his first wife Muriel Kirkland Cotsworth, he illustrated several books before receiving a commission to paint murals in some Washington bowling alleys. It was only after he returned to New York (it was difficult to sell paintings during the Great Depression) that Cotsworth heard “the roar of the greasepaint and the smell of the crowd” and decided that an actor’s life was for him. He began as a member of Eve LeGalliene’s Civic Repertory Theatre, where he appeared in Alice in Wonderland (as The Mad Hatter) and Hedda Gabler. (Two of Staats’ fellow thespians in this troupe were Burgess Meredith and Parker Fennelly.)

It was Abby Lewis who noticed that Staats Cotsworth had a fine voice, and introduced him to some people in the radio industry. Soon, he was playing Jeff Taylor on the daytime drama Pepper Young’s Family. Since many “soaps” were heard five days a week—and since Cotsworth worked on a lot of them—this explains how he was able to run up that 7,500 broadcasts number mentioned earlier. Staats appeared on the likes of Amanda of Honeymoon Hill (as Edward Leighton), Big Sister (Dr. John Wayne), Lone Journey (Wolfe Bennett), Ma Perkins (Gideon Harris), Marriage for Two (Roger Hoyt), The Right to Happiness (Alex Delavan), and When a Girl Marries (Phil Stanley). He also made the rounds on Lorenzo Jones, The Second Mrs. Burton, Stella Dallas, and The Story of Mary Martin. Cotsworth’s most famous daytime gig was portraying the titular reporter on Front Page Ferrell, a role that he held longer than any other actor. (The character had been played in the program’s early run by Richard Widmark.)

It was Abby Lewis who noticed that Staats Cotsworth had a fine voice, and introduced him to some people in the radio industry. Soon, he was playing Jeff Taylor on the daytime drama Pepper Young’s Family. Since many “soaps” were heard five days a week—and since Cotsworth worked on a lot of them—this explains how he was able to run up that 7,500 broadcasts number mentioned earlier. Staats appeared on the likes of Amanda of Honeymoon Hill (as Edward Leighton), Big Sister (Dr. John Wayne), Lone Journey (Wolfe Bennett), Ma Perkins (Gideon Harris), Marriage for Two (Roger Hoyt), The Right to Happiness (Alex Delavan), and When a Girl Marries (Phil Stanley). He also made the rounds on Lorenzo Jones, The Second Mrs. Burton, Stella Dallas, and The Story of Mary Martin. Cotsworth’s most famous daytime gig was portraying the titular reporter on Front Page Ferrell, a role that he held longer than any other actor. (The character had been played in the program’s early run by Richard Widmark.)

His work as the muckraking Ferrell no doubt allowed Staats Cotsworth to move seamlessly into the part of Casey on Crime Photographer, a detective drama that spotlighted the investigative exploits of a shutterbug employed by The Morning Express. Each week, our hero lubricated himself at a dive called The Blue Note—where he hung out with reporter girlfriend Annie Williams and jawed with sardonic bartender Ethelbert. A favorite of listeners between 1943 and 1955, Casey, Crime Photographer was just one of several radio jobs that kept Staats busy. He could also be heard as Lt. Weigand on Mr. and Mrs. North; district attorney Sam Howe on Roger Kilgore, Public Defender; Major Hugh North on The Man from G-2, and the titular heroes on Inspector Thorne and Mark Trail.

His work as the muckraking Ferrell no doubt allowed Staats Cotsworth to move seamlessly into the part of Casey on Crime Photographer, a detective drama that spotlighted the investigative exploits of a shutterbug employed by The Morning Express. Each week, our hero lubricated himself at a dive called The Blue Note—where he hung out with reporter girlfriend Annie Williams and jawed with sardonic bartender Ethelbert. A favorite of listeners between 1943 and 1955, Casey, Crime Photographer was just one of several radio jobs that kept Staats busy. He could also be heard as Lt. Weigand on Mr. and Mrs. North; district attorney Sam Howe on Roger Kilgore, Public Defender; Major Hugh North on The Man from G-2, and the titular heroes on Inspector Thorne and Mark Trail.

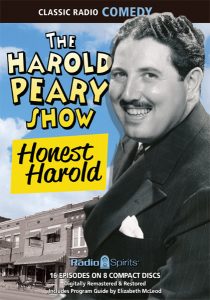

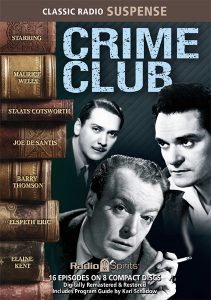

A 1948 Newsweek article on Staats Cotsworth (humorously entitled “Cotsworth in the Chips”) gave the game away as to how well-compensated the actor was for his hectic broadcasting schedule. After a few Casey-style cocktails, Staats let slip enough information to the reporter that allowed any accountant worth his/her salt to estimate that the radio thespian had a weekly income of $1,000—a considerable sum at that time. (For example, Cotsworth was pulling down $250 weekly in his capacity as Casey, Crime Photographer alone.) When asked why he continued to act on daytime dramas, Staats matter-of-factly replied: “Giving up a daytime show is like turning in your insurance policy.” A sample of Cotsworth’s radio resume would include such shows as Best Plays, The Cavalcade of America, The Chase, Crime Club, Dimension X, The Ford Theatre, Grand Central Station, Great Plays, The March of Time, The MGM Theatre of the Air, Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons, The Mysterious Traveler, The NBC Star Playhouse, Rocky Fortune, Rogue’s Gallery, Secret Missions, The Shadow, The Silver Theatre, The Sportsmen’s Club, The Theatre Guild on the Air, Words at War, You are There, and You Make the News.

A 1948 Newsweek article on Staats Cotsworth (humorously entitled “Cotsworth in the Chips”) gave the game away as to how well-compensated the actor was for his hectic broadcasting schedule. After a few Casey-style cocktails, Staats let slip enough information to the reporter that allowed any accountant worth his/her salt to estimate that the radio thespian had a weekly income of $1,000—a considerable sum at that time. (For example, Cotsworth was pulling down $250 weekly in his capacity as Casey, Crime Photographer alone.) When asked why he continued to act on daytime dramas, Staats matter-of-factly replied: “Giving up a daytime show is like turning in your insurance policy.” A sample of Cotsworth’s radio resume would include such shows as Best Plays, The Cavalcade of America, The Chase, Crime Club, Dimension X, The Ford Theatre, Grand Central Station, Great Plays, The March of Time, The MGM Theatre of the Air, Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons, The Mysterious Traveler, The NBC Star Playhouse, Rocky Fortune, Rogue’s Gallery, Secret Missions, The Shadow, The Silver Theatre, The Sportsmen’s Club, The Theatre Guild on the Air, Words at War, You are There, and You Make the News.

As you can probably gather from the preceding paragraph, Staats Cotsworth didn’t let any grass grow under his feet where radio was concerned…so it’s not too surprising that the movies in which he appeared—That Night! (1957), Peyton Place (1957), They Might Be Giants (1971)—were made long after radio was giving way to TV. Cotsworth would do quite a bit of small screen work (playing judges and other authority figures), appearing on shows like The Defenders, Dr. Kildare, and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. In addition, he returned to what many have said was his true love—the stage, where he appeared in productions of Advise and Consent (1960) and The Right Honourable Gentleman (1965). Staats would never abandon the medium that rewarded him the most, however; he appeared on shows that closed out Radio’s Golden Age (like The CBS Radio Workshop and X-Minus One) and on attempts to keep radio alive (like The Eternal Light and Theatre Five). One of his final performing jobs would be on The CBS Radio Mystery Theatre before his death in 1979 at the age of 71.

As you can probably gather from the preceding paragraph, Staats Cotsworth didn’t let any grass grow under his feet where radio was concerned…so it’s not too surprising that the movies in which he appeared—That Night! (1957), Peyton Place (1957), They Might Be Giants (1971)—were made long after radio was giving way to TV. Cotsworth would do quite a bit of small screen work (playing judges and other authority figures), appearing on shows like The Defenders, Dr. Kildare, and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. In addition, he returned to what many have said was his true love—the stage, where he appeared in productions of Advise and Consent (1960) and The Right Honourable Gentleman (1965). Staats would never abandon the medium that rewarded him the most, however; he appeared on shows that closed out Radio’s Golden Age (like The CBS Radio Workshop and X-Minus One) and on attempts to keep radio alive (like The Eternal Light and Theatre Five). One of his final performing jobs would be on The CBS Radio Mystery Theatre before his death in 1979 at the age of 71.

An obituary for Staats Cotsworth in The St. Petersburg Times noted that he was “an accomplished painter of oils and watercolors” and was even listed in the current edition of Who’s Who in American Art. But here at Radio Spirits, we remember today’s birthday boy for his lofty accomplishments in the ether, beginning with his trademark role as Casey, Crime Photographer in the collection Blue Note. Check out Mr. Cotsworth also in Crime Club, Dimension X: Adventures in Time & Space, The Mysterious Traveler: Dark Destiny, Words at War, and X-Minus One: Time and Time Again. Our Stop the Press! compendium features a pair of Casey, Crime Photographer broadcasts from 1947, and on Great Radio Science Fiction, Cotsworth is among the cast in a two-part adaptation of Frederick Pohl’s classic “The Space Merchants” from The CBS Radio Workshop. Happy birthday, Staats!

An obituary for Staats Cotsworth in The St. Petersburg Times noted that he was “an accomplished painter of oils and watercolors” and was even listed in the current edition of Who’s Who in American Art. But here at Radio Spirits, we remember today’s birthday boy for his lofty accomplishments in the ether, beginning with his trademark role as Casey, Crime Photographer in the collection Blue Note. Check out Mr. Cotsworth also in Crime Club, Dimension X: Adventures in Time & Space, The Mysterious Traveler: Dark Destiny, Words at War, and X-Minus One: Time and Time Again. Our Stop the Press! compendium features a pair of Casey, Crime Photographer broadcasts from 1947, and on Great Radio Science Fiction, Cotsworth is among the cast in a two-part adaptation of Frederick Pohl’s classic “The Space Merchants” from The CBS Radio Workshop. Happy birthday, Staats!