Happy Birthday, Frances Robinson!

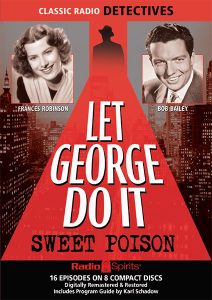

“Danger’s my stock-in-trade,” observed George Valentine weekly on the popular Mutual crime drama Let George Do It. For actress Frances Robinson, who played George’s loyal gal Friday, Claire “Brooksie” Brooks, her stock-in-trade was playing girlfriends and secretaries (and in some cases both) on radio. From Perry Mason to Murder and Mr. Malone, Robinson supplemented a busy movie career with multiple trips to emote before a radio microphone. Born Marion Frances Ladd on this date in 1916, Frances entered show business at the age of five, playing the younger version of Lillian Gish’s character in D.W. Griffith’s classic Orphans of the Storm (1921).

Frances Robinson was born in Fort Wadsworth, NY—a military base where her father served as a sergeant in the U.S. Army. When the senior Ladd passed away in 1925, Frances and her mother made a trek to California. The child actress made a few more appearances in films (Laddie [1926], The Climbers [1927]) before taking a hiatus from motion pictures. Robinson worked as an illustrator’s model for a time (and did stock theatre work in NYC), then returned to the movies in 1935. When she signed a contract with Universal Pictures in 1937, she began using “Frances Robinson” as her professional name (she went by “Marion Ladd” in a 1935 Paramount film, Millions in the Air).

Frances Robinson was born in Fort Wadsworth, NY—a military base where her father served as a sergeant in the U.S. Army. When the senior Ladd passed away in 1925, Frances and her mother made a trek to California. The child actress made a few more appearances in films (Laddie [1926], The Climbers [1927]) before taking a hiatus from motion pictures. Robinson worked as an illustrator’s model for a time (and did stock theatre work in NYC), then returned to the movies in 1935. When she signed a contract with Universal Pictures in 1937, she began using “Frances Robinson” as her professional name (she went by “Marion Ladd” in a 1935 Paramount film, Millions in the Air).

At Universal, ingenue Frances Robinson was kept pretty busy in both B-Westerns (Forbidden Valley [1938]) and programmers (Society Smugglers [1939]), and cliffhanger serial fans fondly remember her as the spunky female lead in both Tim Tyler’s Luck (1937) and Red Barry (1938; as girl reporter “Mississippi”). (You may have caught this last chapter play on TCM on Saturday mornings in recent months.) Frances also played leading lady to Johnny Mack Brown in two of his oaters, Desperate Trails (1939) and Riders of Pasco Basin (1940)—again, if you watch as many old movies as I do, you might have caught Riders recently on Starz Encore Westerns. Robinson would leave Universal at the beginning of the decade to freelance (she did a few programmers for Columbia, including The Lone Wolf Keeps a Date and a Joe E. Brown comedy, So You Won’t Talk [both 1940]), which would give her an opportunity to appear in two “prestige” films at MGM, Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde (1941; the Spencer Tracy-Ingrid Berman version) and Smilin’ Through (1941).

About this same time, Frances Robinson began her rewarding radio career with appearances on The Silver Theatre and The Lux Radio Theatre. She worked with Maurice Tarplin, Larry Haines, and Roger DeKoven on the Ziv-syndicated crime drama Manhunt. Frances put her movie career away in mothballs during WW2 after getting work at Lockheed Aircraft in the personnel placement department. Radio proved a good fit for Robinson, and it would nicely accommodate both her later stage work (she was in a 1944 Broadway musical, Jackpot) and an advertising job she acquired after WW2. Frances was “Ellen Deering” to Jose Ferrer’s “Philo Vance” in the short-lived NBC series based on the S.S. Van Dine creation in 1945, and later appeared opposite Frank Lovejoy (as “hep” secretary Maggie) in Murder and Mr. Malone, an ABC program based on Craig Rice’s sleuth.

About this same time, Frances Robinson began her rewarding radio career with appearances on The Silver Theatre and The Lux Radio Theatre. She worked with Maurice Tarplin, Larry Haines, and Roger DeKoven on the Ziv-syndicated crime drama Manhunt. Frances put her movie career away in mothballs during WW2 after getting work at Lockheed Aircraft in the personnel placement department. Radio proved a good fit for Robinson, and it would nicely accommodate both her later stage work (she was in a 1944 Broadway musical, Jackpot) and an advertising job she acquired after WW2. Frances was “Ellen Deering” to Jose Ferrer’s “Philo Vance” in the short-lived NBC series based on the S.S. Van Dine creation in 1945, and later appeared opposite Frank Lovejoy (as “hep” secretary Maggie) in Murder and Mr. Malone, an ABC program based on Craig Rice’s sleuth.

“If I was on the air it was a mystery,” Frances Robinson joked to Radio Life (after dubbing her a “mystery girl”) about the time she started playing “Brooksie” on Let George Do It—which remains her best-remembered radio showcase. (Frances would later be replaced on George by Virginia Gregg…which seems only fair, since Robinson replaced Gregg temporarily on Richard Diamond, Private Detective playing girlfriend Helen Asher.) Robinson had regular “girlfriend” roles on Perry Mason, Ellery Queen, and The Falcon, and to further her crime drama credentials she also worked on The Adventures of Philip Marlowe, The Adventures of the Saint, Jeff Regan, Investigator, and Mike Malloy. But Frances was nothing if not versatile; she demonstrated a flair for comedy, filling in for Bea Benaderet as “Eve Goodwin” on The Great Gildersleeve briefly in 1947 during Benaderet’s pregnancy. Rounding out Robinson’s radio resume: shows like The Camel Screen Guild Theatre, The Cavalcade of America, Hallmark Playhouse, Romance, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, Songs by Sinatra, and The Whistler.

“If I was on the air it was a mystery,” Frances Robinson joked to Radio Life (after dubbing her a “mystery girl”) about the time she started playing “Brooksie” on Let George Do It—which remains her best-remembered radio showcase. (Frances would later be replaced on George by Virginia Gregg…which seems only fair, since Robinson replaced Gregg temporarily on Richard Diamond, Private Detective playing girlfriend Helen Asher.) Robinson had regular “girlfriend” roles on Perry Mason, Ellery Queen, and The Falcon, and to further her crime drama credentials she also worked on The Adventures of Philip Marlowe, The Adventures of the Saint, Jeff Regan, Investigator, and Mike Malloy. But Frances was nothing if not versatile; she demonstrated a flair for comedy, filling in for Bea Benaderet as “Eve Goodwin” on The Great Gildersleeve briefly in 1947 during Benaderet’s pregnancy. Rounding out Robinson’s radio resume: shows like The Camel Screen Guild Theatre, The Cavalcade of America, Hallmark Playhouse, Romance, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, Songs by Sinatra, and The Whistler.

Frances Robinson would eventually return to motion pictures. She’s in The Missing Lady (1946) (an entry in Monogram’s Shadow series loosely based on the radio program), Keeper of the Bees (1947) and Backfire (1950). In the 1950s, Robinson was more at home on the small screen, with appearances on many of the popular dramatic anthologies of that era (Armstrong Circle Theatre, Kraft Television Theatre), and as the commercial spokeswoman for Arrid Deodorant. Frances would make the rounds in guest shots on such shows as The Millionaire and The Real McCoys. In the Howard Duff and Ida Lupino sitcom Mr. Adams and Eve, Robinson had a recurring role as next-door neighbor “Louise Stewart.” Robinson continued to work in the 1960s on such television venues as The Donna Reed Show and Dr. Kildare, while making an occasional feature film appearance (she played “Aunt Gladys” in the Disney release The Happiest Millionaire [1967]). Sadly, Frances left this world far too early in 1971 at the age of 55.

Frances Robinson would eventually return to motion pictures. She’s in The Missing Lady (1946) (an entry in Monogram’s Shadow series loosely based on the radio program), Keeper of the Bees (1947) and Backfire (1950). In the 1950s, Robinson was more at home on the small screen, with appearances on many of the popular dramatic anthologies of that era (Armstrong Circle Theatre, Kraft Television Theatre), and as the commercial spokeswoman for Arrid Deodorant. Frances would make the rounds in guest shots on such shows as The Millionaire and The Real McCoys. In the Howard Duff and Ida Lupino sitcom Mr. Adams and Eve, Robinson had a recurring role as next-door neighbor “Louise Stewart.” Robinson continued to work in the 1960s on such television venues as The Donna Reed Show and Dr. Kildare, while making an occasional feature film appearance (she played “Aunt Gladys” in the Disney release The Happiest Millionaire [1967]). Sadly, Frances left this world far too early in 1971 at the age of 55.

To commemorate Frances Robinson’s natal anniversary today, Radio Spirits invites you to check out her signature role as “Brooksie” on Let George Do It with our CD collections Cry Uncle and Sweet Poison. You can also find our birthday girl on the Richard Diamond, Private Detective sets Dead Men and Homicide Made Easy, and on The Adventures of Philip Marlowe (Night Tide), Broadway’s My Beat (Great White Way), Jeff Regan, Investigator (Stand By for Mystery), and The Damon Runyon Theatre (Here is Broadway). Happy birthday, Frances!

To commemorate Frances Robinson’s natal anniversary today, Radio Spirits invites you to check out her signature role as “Brooksie” on Let George Do It with our CD collections Cry Uncle and Sweet Poison. You can also find our birthday girl on the Richard Diamond, Private Detective sets Dead Men and Homicide Made Easy, and on The Adventures of Philip Marlowe (Night Tide), Broadway’s My Beat (Great White Way), Jeff Regan, Investigator (Stand By for Mystery), and The Damon Runyon Theatre (Here is Broadway). Happy birthday, Frances!