Happy Birthday, Ed Gardner!

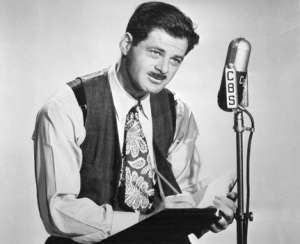

It was on a short-lived radio series entitled This is New York that comedian Ed Gardner found his creative muse…playing a pugnacious New Yorker who answered to “Archie.” Gardner was the show’s producer, and he’d be the first to admit that he was no actor—the only problem was, he wasn’t able to find a suitable thespian to play the role. Ed decided to read the part himself in rehearsal, and in so doing convulsed the cast and crew to the point where it was clear he was the only person capable of doing the job. “Archie” would later become the starring character in a situation comedy entitled Duffy’s Tavern, and make the man born in Astoria, NY (Long Island, you know) on this date in 1901 a household name.

Ed Gardner was born Friedrich Poggenburg, Jr….clearly, he made the right call in changing his name, which he did about the time he entered show business. Before that, “Poggy” (as he was known to very close friends) received a formal education at both P.S. 4 and William Cullen Bryant High School…up to a point. You see, the Family Poggenburg encouraged Ed to make his mark in the world without a lot of “fancy book learning,” and at age 14 Ed got a gig playing piano in a neighborhood saloon. Prohibition sadly put an end to those activities, and like the quintessential hustler he’d later play on Duffy’s, Gardner soon embarked on a “jack-of-all-trades” tour that included jobs as a railroad dispatcher, a stenographer…and endless sales opportunities, peddling everything from pianos to paint.

Ed Gardner was born Friedrich Poggenburg, Jr….clearly, he made the right call in changing his name, which he did about the time he entered show business. Before that, “Poggy” (as he was known to very close friends) received a formal education at both P.S. 4 and William Cullen Bryant High School…up to a point. You see, the Family Poggenburg encouraged Ed to make his mark in the world without a lot of “fancy book learning,” and at age 14 Ed got a gig playing piano in a neighborhood saloon. Prohibition sadly put an end to those activities, and like the quintessential hustler he’d later play on Duffy’s, Gardner soon embarked on a “jack-of-all-trades” tour that included jobs as a railroad dispatcher, a stenographer…and endless sales opportunities, peddling everything from pianos to paint.

Ed Gardner did well enough to divert the wolf at the door, but money seemed to run through his fingers. Things really didn’t take off for him until he married actress Shirley Booth in 1929. Booth was an ambitious performer who dreamed of conquering Broadway, and although she wasn’t particularly sold on her husband developing the same talent, Ed was determined to make his name in show business as well (banking on his fast patter and talent for ingratiating himself with people). It wasn’t long before Gardner found work as a theatrical publicist, and from that he got into radio as a producer with the J. Walter Thompson agency — working on shows with the likes of Bing Crosby, George Burns, and Gracie Allen. Along the way, he made the acquaintance of writer Abe Burrows, whose sardonic style of comedy appealed to Ed. The two men pooled their talents on This is New York in 1938. The series didn’t last long, but the “Archie” creation of Gardner’s became popular enough to make later appearances on Good News of 1940 and Forecast (which devoted a half-hour to a pilot that ultimately became Duffy’s Tavern).

Ed Gardner did well enough to divert the wolf at the door, but money seemed to run through his fingers. Things really didn’t take off for him until he married actress Shirley Booth in 1929. Booth was an ambitious performer who dreamed of conquering Broadway, and although she wasn’t particularly sold on her husband developing the same talent, Ed was determined to make his name in show business as well (banking on his fast patter and talent for ingratiating himself with people). It wasn’t long before Gardner found work as a theatrical publicist, and from that he got into radio as a producer with the J. Walter Thompson agency — working on shows with the likes of Bing Crosby, George Burns, and Gracie Allen. Along the way, he made the acquaintance of writer Abe Burrows, whose sardonic style of comedy appealed to Ed. The two men pooled their talents on This is New York in 1938. The series didn’t last long, but the “Archie” creation of Gardner’s became popular enough to make later appearances on Good News of 1940 and Forecast (which devoted a half-hour to a pilot that ultimately became Duffy’s Tavern).

While working as the producer on Rudy Vallee’s Sealtest variety program, Ed Gardner received word from the Schick Razors people that they were interested in sponsoring a Duffy’s Tavern series. Ahead of the March 1, 1941 premiere over CBS, Gardner tapped his buddy Ace Burrows to be the head writer. The two men assembled both an impressive writing staff and supporting cast. Charlie Cantor (one of Fred Allen’s prized stooges) was heard as the stupefyingly dense Clifton Finnegan (his name was a parody of the host of Information Please), and veteran African-American comic Eddie Green became “Eddie the waiter.” Gardner also cast his spouse Shirley Booth as “Miss Duffy,” the daughter of the tavern’s owner. She was there the keep a close eye on things, because (as we were informed every week) “Duffy ain’t here.” Ed presided over the weekly half-hour proceedings as “Archie the manager,” a fast-talking con man constantly searching for ways to rise above his lowly (serving) station. Booth didn’t stay with Duffy’s Tavern for long (nor did her marriage to Ed last), and while Gardner welcomed a slew of fine comic actresses to fill the void (including Florence Halop, Sara Berner, Sandra Gould, and Doris Singleton), he often lamented that Shirley’s shoes were hard to fill.

While working as the producer on Rudy Vallee’s Sealtest variety program, Ed Gardner received word from the Schick Razors people that they were interested in sponsoring a Duffy’s Tavern series. Ahead of the March 1, 1941 premiere over CBS, Gardner tapped his buddy Ace Burrows to be the head writer. The two men assembled both an impressive writing staff and supporting cast. Charlie Cantor (one of Fred Allen’s prized stooges) was heard as the stupefyingly dense Clifton Finnegan (his name was a parody of the host of Information Please), and veteran African-American comic Eddie Green became “Eddie the waiter.” Gardner also cast his spouse Shirley Booth as “Miss Duffy,” the daughter of the tavern’s owner. She was there the keep a close eye on things, because (as we were informed every week) “Duffy ain’t here.” Ed presided over the weekly half-hour proceedings as “Archie the manager,” a fast-talking con man constantly searching for ways to rise above his lowly (serving) station. Booth didn’t stay with Duffy’s Tavern for long (nor did her marriage to Ed last), and while Gardner welcomed a slew of fine comic actresses to fill the void (including Florence Halop, Sara Berner, Sandra Gould, and Doris Singleton), he often lamented that Shirley’s shoes were hard to fill.

Duffy’s Tavern would soon become one of radio’s most popular radio comedy shows. It justly acquired a reputation as a smartly-written series, and Hollywood celebrities jumped at the opportunity to visit the famed Manhattan dive to be insulted by Archie (while garnering huge laughs in the process). A number of Tinseltown’s top stars made cameos in a 1945 motion picture based on the film, and while the merits of the movie are often debated (Gardner himself didn’t care for it), the participation of so many film personalities (Alan Ladd, Veronica Lake) ensured a big box office take. (Ed later tried his hand at producing motion pictures with a 1951 feature, The Man With My Face—but it turned out to be a notorious flop.) In addition to his weekly duties bragging to audiences that Duffy’s was “where the elite meet to eat,” Gardner made the rounds on such shows as The Big Show, The Camel Comedy Caravan, The Columbia Workshop, Command Performance, Jubilee, The Kraft Music Hall, Mail Call, Paul Whiteman Presents, The Radio Hall of Fame, The Sealtest Variety Theatre, and Suspense (“The Palmer Method”). Ed was also made welcome on shows headlined by Fred Allen, Dick Haymes, Kate Smith, and Alan Young.

Duffy’s Tavern would soon become one of radio’s most popular radio comedy shows. It justly acquired a reputation as a smartly-written series, and Hollywood celebrities jumped at the opportunity to visit the famed Manhattan dive to be insulted by Archie (while garnering huge laughs in the process). A number of Tinseltown’s top stars made cameos in a 1945 motion picture based on the film, and while the merits of the movie are often debated (Gardner himself didn’t care for it), the participation of so many film personalities (Alan Ladd, Veronica Lake) ensured a big box office take. (Ed later tried his hand at producing motion pictures with a 1951 feature, The Man With My Face—but it turned out to be a notorious flop.) In addition to his weekly duties bragging to audiences that Duffy’s was “where the elite meet to eat,” Gardner made the rounds on such shows as The Big Show, The Camel Comedy Caravan, The Columbia Workshop, Command Performance, Jubilee, The Kraft Music Hall, Mail Call, Paul Whiteman Presents, The Radio Hall of Fame, The Sealtest Variety Theatre, and Suspense (“The Palmer Method”). Ed was also made welcome on shows headlined by Fred Allen, Dick Haymes, Kate Smith, and Alan Young.

In 1949, Ed Gardner decided to move production of Duffy’s Tavern to Puerto Rico, which allowed him to take advantage of the country’s favorable tax laws. In hindsight, it may have been a sound business decision, but the relocation hurt the program: Eddie Green passed away not long after the move, Gardner had trouble keeping writers on staff, and unless a celebrity was in the mood for a nice vacation getting big stars to appear on the program was a challenge. Television also began to threaten the show’s sponsorship, and when the series left NBC on December 28, 1951, Gardner decided to give TV a try with a video version of Duffy’s that was syndicated between 1954 and 1955. Although Ed made a few more TV appearances after the cancellation of the TV Duffy’s (including two episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents), his failing health curtailed much of his show business activity. He left this world for a better one on August 17, 1963 at the age of 62.

In 1949, Ed Gardner decided to move production of Duffy’s Tavern to Puerto Rico, which allowed him to take advantage of the country’s favorable tax laws. In hindsight, it may have been a sound business decision, but the relocation hurt the program: Eddie Green passed away not long after the move, Gardner had trouble keeping writers on staff, and unless a celebrity was in the mood for a nice vacation getting big stars to appear on the program was a challenge. Television also began to threaten the show’s sponsorship, and when the series left NBC on December 28, 1951, Gardner decided to give TV a try with a video version of Duffy’s that was syndicated between 1954 and 1955. Although Ed made a few more TV appearances after the cancellation of the TV Duffy’s (including two episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents), his failing health curtailed much of his show business activity. He left this world for a better one on August 17, 1963 at the age of 62.

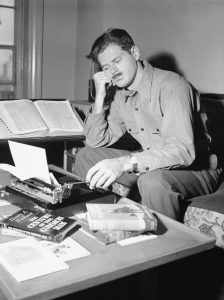

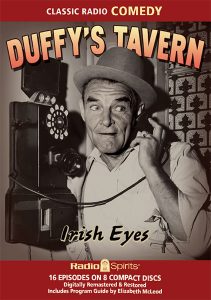

“Comedy writing is a labor of love of black coffee,” Ed Gardner once joked about his profession. The stories of Gardner being a tough taskmaster are legion (I recommend a purchase of Jordan R. Young’s The Laugh Crafters for some anecdotes that we can’t quite quote appropriately here), but his radio creation of Duffy’s Tavern remains of the medium’s funniest shows. Our birthday boy is held in high regard as a first-rate editor who knew funny when he heard it. For the skeptics in the audience, I also recommend the Radio Spirits collections Duffy Ain’t Here and our newest compendium Irish Eyes for their large belly laugh quotient. If you’d like to learn more about the history behind the Tavern, leave us invest in a copy of Duffy’s Tavern: A History of Ed Gardner’s Radio Program, written by Radio Spirits’ own Martin Grams, Jr. Happy Birthday, Ed!

“Comedy writing is a labor of love of black coffee,” Ed Gardner once joked about his profession. The stories of Gardner being a tough taskmaster are legion (I recommend a purchase of Jordan R. Young’s The Laugh Crafters for some anecdotes that we can’t quite quote appropriately here), but his radio creation of Duffy’s Tavern remains of the medium’s funniest shows. Our birthday boy is held in high regard as a first-rate editor who knew funny when he heard it. For the skeptics in the audience, I also recommend the Radio Spirits collections Duffy Ain’t Here and our newest compendium Irish Eyes for their large belly laugh quotient. If you’d like to learn more about the history behind the Tavern, leave us invest in a copy of Duffy’s Tavern: A History of Ed Gardner’s Radio Program, written by Radio Spirits’ own Martin Grams, Jr. Happy Birthday, Ed!