Happy Birthday, Alan Ladd!

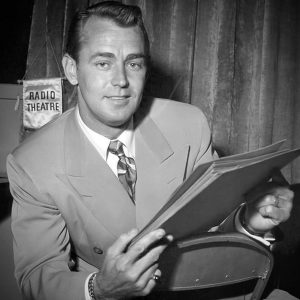

Old-time radio legend Frank Nelson (The Jack Benny Program) shared the following anecdote in Leonard Maltin’s The Great American Broadcast: “I had a friend who did just bits with me in radio shows, and one day he said, ‘Frank, I have a chance to do some [motion] pictures, what do you think I ought to do? Do you think I should stay in radio or do you think I should do the picture thing?’ And I was thinking, ‘Boy, he reads in a monotone; if he can do anything in pictures’—and I didn’t think he could—’he sure ought to take that.’ Well, fortunately he did, and he did very well for himself; his name was Alan Ladd.”

Alan Walbridge Ladd was born in Hot Springs, Arkansas on this date in 1913. He was the only child of Alan Ladd and Ina Raleigh (also known as Selina Rowley), and his childhood was an unhappy one. Young Alan lost his father to a heart attack when he was four years old. A year later, the family’s home burned to the ground—Alan had been playing with matches. His mother would remarry sometime later to Jim Beavers, a housepainter, and the Ladd clan was forced to move from Oklahoma City to California due to economic hardship. In the San Fernando Valley, Beavers found work at the FBO Studios as a painter, and Ladd would enroll at North Hollywood High where his extracurricular pursuits included swimming and diving.

Alan Walbridge Ladd was born in Hot Springs, Arkansas on this date in 1913. He was the only child of Alan Ladd and Ina Raleigh (also known as Selina Rowley), and his childhood was an unhappy one. Young Alan lost his father to a heart attack when he was four years old. A year later, the family’s home burned to the ground—Alan had been playing with matches. His mother would remarry sometime later to Jim Beavers, a housepainter, and the Ladd clan was forced to move from Oklahoma City to California due to economic hardship. In the San Fernando Valley, Beavers found work at the FBO Studios as a painter, and Ladd would enroll at North Hollywood High where his extracurricular pursuits included swimming and diving.

Alan Ladd also dabbled in high school dramatics. His performance as “Koko” in a production of The Mikado attracted the attention of a talent scout with Universal Pictures, who signed Ladd and a number of other young hopefuls to a contract (with options that could last up until seven years). Though Alan did work uncredited in one movie—Once in a Lifetime (1932), as a projectionist—the studio dropped him after six months (they thought he was too short). (Probably not the wisest decision in hindsight: though one of Ladd’s fellow “discoveries” also got a pink slip—Tyrone Power.) Alan graduated from high school in 1934, and from there embarked on a number of careers, including a stint as the advertising manager of a newspaper and a cash register salesman. Ladd was anxious to get back into the film industry, and he worked at Warner Bros. as a grip for two years before a scaffold accident convinced him to quit.

Alan Ladd’s radio career was the result of his taking acting lessons at a school run by Ben Bard—an old crony from Ladd’s Universal days who cast the young performer in a number of stage productions. Bard also persuaded Alan to speak in a lower register (he described Ladd as “a shy guy”) and pretty soon the actor was performing regularly on KFWB, the Warner Bros. studio-owned station. (In his time with KFWB, Alan would work as many as 20 shows a week—including a stint as “The Richfield Reporter.”) Ladd hadn’t completely abandoned the idea of becoming a film actor—he can be glimpsed in the 1936 20th Century-Fox musical Pigskin Parade, among other films—but his silver screen dreams wouldn’t fully blossom until agent Sue Carol entered his life.

Alan Ladd’s radio career was the result of his taking acting lessons at a school run by Ben Bard—an old crony from Ladd’s Universal days who cast the young performer in a number of stage productions. Bard also persuaded Alan to speak in a lower register (he described Ladd as “a shy guy”) and pretty soon the actor was performing regularly on KFWB, the Warner Bros. studio-owned station. (In his time with KFWB, Alan would work as many as 20 shows a week—including a stint as “The Richfield Reporter.”) Ladd hadn’t completely abandoned the idea of becoming a film actor—he can be glimpsed in the 1936 20th Century-Fox musical Pigskin Parade, among other films—but his silver screen dreams wouldn’t fully blossom until agent Sue Carol entered his life.

Sue Carol heard Alan Ladd performing on KFWB one night (in a play where he portrayed both the father and son) and was so impressed with his looks after meeting him that she took him on as a client, getting him work in such films as Riders of the Sea (1939) and The Light of Western Stars (1940). Many motion picture appearances followed: Those Were the Days! (1940), Captain Caution (1940), The Black Cat (1941), etc. If you’re familiar with Citizen Kane (1941), you might be interested to know that the reporter smoking a pipe (in silhouette) is Ladd (his voice is a dead giveaway).

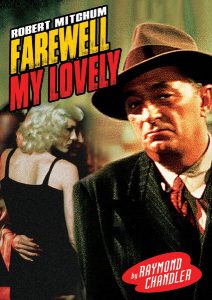

With a small but memorable role in Joan of Paris (1942), Alan Ladd was offered a $400-a-week contract at R-K-O…but he received a better offer at Paramount, where he would make the movie that put him on the map. The studio changed the title of Graham Greene’s novel A Gun for Sale to This Gun for Hire (1942), with Alan cast as a sympathetic hitman named “Raven.” Though Robert Preston was the nominal male lead in the film, Ladd stole the picture with his killer-with-a-conscience character, paired with actress Veronica Lake with whom he shared a remarkable chemistry. (Lake’s 4’11” height was also more suitable to Alan’s 5’6” frame.) This Gun for Hire proved such a success at the box office that Ladd and Lake were re-teamed for a following film, The Glass Key (1942)—based on Dashiell Hammett’s novel (and previously filmed in 1935 with George Raft).

With a small but memorable role in Joan of Paris (1942), Alan Ladd was offered a $400-a-week contract at R-K-O…but he received a better offer at Paramount, where he would make the movie that put him on the map. The studio changed the title of Graham Greene’s novel A Gun for Sale to This Gun for Hire (1942), with Alan cast as a sympathetic hitman named “Raven.” Though Robert Preston was the nominal male lead in the film, Ladd stole the picture with his killer-with-a-conscience character, paired with actress Veronica Lake with whom he shared a remarkable chemistry. (Lake’s 4’11” height was also more suitable to Alan’s 5’6” frame.) This Gun for Hire proved such a success at the box office that Ladd and Lake were re-teamed for a following film, The Glass Key (1942)—based on Dashiell Hammett’s novel (and previously filmed in 1935 with George Raft).

Alan Ladd made three additional Paramount films—Lucky Jordan (1942), Star Spangled Rhythm (1942; a cameo), and China (1943)—before getting his “Greetings” notice from Uncle Sam. A history of stomach troubles technically earned Ladd a 4-F designation, though he did serve briefly in the United States Army Air Forces First Motion Picture Unit. Alan returned to his motion picture career with And Now Tomorrow (1944), then found himself re-classified 1-A after taking an Army physical. This meant that he would eventually be re-drafted. Paramount, concerned about their star, postponed the inevitable with a series of deferments in order to allow Ladd to make Two Years Before the Mast (made in 1944 but released two years later), Salty O’Rourke (1945), and the all-star Duffy’s Tavern (1945). But by the time he completed The Blue Dahlia (1946)—his fourth with Veronica Lake—a directive from the U.S. Army released all men over the age of 30 from military service, allowing Alan to continue with films like O.S.S. (1946) and Calcutta (1947).

Alan Ladd made three additional Paramount films—Lucky Jordan (1942), Star Spangled Rhythm (1942; a cameo), and China (1943)—before getting his “Greetings” notice from Uncle Sam. A history of stomach troubles technically earned Ladd a 4-F designation, though he did serve briefly in the United States Army Air Forces First Motion Picture Unit. Alan returned to his motion picture career with And Now Tomorrow (1944), then found himself re-classified 1-A after taking an Army physical. This meant that he would eventually be re-drafted. Paramount, concerned about their star, postponed the inevitable with a series of deferments in order to allow Ladd to make Two Years Before the Mast (made in 1944 but released two years later), Salty O’Rourke (1945), and the all-star Duffy’s Tavern (1945). But by the time he completed The Blue Dahlia (1946)—his fourth with Veronica Lake—a directive from the U.S. Army released all men over the age of 30 from military service, allowing Alan to continue with films like O.S.S. (1946) and Calcutta (1947).

A high-profile film star like Alan Ladd naturally found himself in demand where radio was concerned…and his previous experience proved invaluable when he had to reprise both his own film roles and others on dramatic anthologies like The Cavalcade of America, Hollywood Star Time, The Lady Esther/Camel Screen Guild Theatre, The Lux Radio Theatre, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, The Silver Theatre, and Theatre of Romance. Ladd appeared on Suspense four times, and guest starred on the likes of Command Performance and G.I. Journal. In addition, he spoofed his “tough guy” image while joshing with the likes of Abbott & Costello, Jack Benny, Burns & Allen, Eddie Cantor, Ed Gardner (Duffy’s Tavern), Dinah Shore, and Rudy Vallee.

A high-profile film star like Alan Ladd naturally found himself in demand where radio was concerned…and his previous experience proved invaluable when he had to reprise both his own film roles and others on dramatic anthologies like The Cavalcade of America, Hollywood Star Time, The Lady Esther/Camel Screen Guild Theatre, The Lux Radio Theatre, Screen Directors’ Playhouse, The Silver Theatre, and Theatre of Romance. Ladd appeared on Suspense four times, and guest starred on the likes of Command Performance and G.I. Journal. In addition, he spoofed his “tough guy” image while joshing with the likes of Abbott & Costello, Jack Benny, Burns & Allen, Eddie Cantor, Ed Gardner (Duffy’s Tavern), Dinah Shore, and Rudy Vallee.

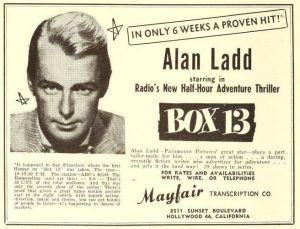

Alan Ladd’s most famous radio contribution came in the form of an adventure series entitled Box 13, a syndicated program from Mayfair Productions. (“Mayfair” had been the name of a chain of restaurants the actor invested in with his old friend Bernie Joslin.) Box 13 featured “Laddie” as Dan Holiday, a retired-newspaper-reporter-turned-mystery-novelist who got inspiration for his books with the insertion of a simple ad in his local paper: “Adventure wanted. Will go anywhere, do anything. Box 13.” Although the series was produced for syndication, the series aired on both the West and East Coast Mutual networks. The strides made in transcribing shows for later broadcast meant that Alan did not need to not be tied down to a weekly series. Thus he was able to star in such films as Saigon (1948; his final teaming with Veronica Lake), Whispering Smith (1948), The Great Gatsby (1949), and Chicago Deadline (1949).

Alan Ladd’s most famous radio contribution came in the form of an adventure series entitled Box 13, a syndicated program from Mayfair Productions. (“Mayfair” had been the name of a chain of restaurants the actor invested in with his old friend Bernie Joslin.) Box 13 featured “Laddie” as Dan Holiday, a retired-newspaper-reporter-turned-mystery-novelist who got inspiration for his books with the insertion of a simple ad in his local paper: “Adventure wanted. Will go anywhere, do anything. Box 13.” Although the series was produced for syndication, the series aired on both the West and East Coast Mutual networks. The strides made in transcribing shows for later broadcast meant that Alan did not need to not be tied down to a weekly series. Thus he was able to star in such films as Saigon (1948; his final teaming with Veronica Lake), Whispering Smith (1948), The Great Gatsby (1949), and Chicago Deadline (1949).

Alan Ladd’s movie work didn’t slow down in the 1950s…and yet he wasn’t the big marquee name that distinguished his career in the previous decade. Ladd appeared in film noirs like Captain Carey, U.S.A. (1950) and Appointment with Danger (1951), and graced westerns like Drum Beat (1954) and The Proud Rebel (1958). His best cinematic turn at this time was his starring role in Shane (1953), considered by many to be one of the finest westerns in movie history. Ladd kept working and his final film, The Carpetbaggers (1964), was released a few months after his death in January of that year—Alan succumbed to an accidental overdose of alcohol and barbiturates at the age of 50.

Alan Ladd’s movie work didn’t slow down in the 1950s…and yet he wasn’t the big marquee name that distinguished his career in the previous decade. Ladd appeared in film noirs like Captain Carey, U.S.A. (1950) and Appointment with Danger (1951), and graced westerns like Drum Beat (1954) and The Proud Rebel (1958). His best cinematic turn at this time was his starring role in Shane (1953), considered by many to be one of the finest westerns in movie history. Ladd kept working and his final film, The Carpetbaggers (1964), was released a few months after his death in January of that year—Alan succumbed to an accidental overdose of alcohol and barbiturates at the age of 50.

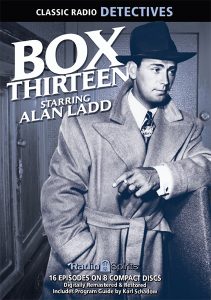

Alan Ladd’s signature role as Dan Holiday is spotlighted in the Radio Spirits collection Box 13; this 8-CD set features the first sixteen episodes of the series. But you can also hear today’s birthday boy in a funny George Burns & Gracie Allen broadcast from March 7, 1944) on Burns & Allen and Friends, and an adaptation of “The Glass Key” from The Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre (07/22/46), which you’ll find on Smithsonian Legendary Performers: Dashiell Hammett. Happy birthday, Alan!

Alan Ladd’s signature role as Dan Holiday is spotlighted in the Radio Spirits collection Box 13; this 8-CD set features the first sixteen episodes of the series. But you can also hear today’s birthday boy in a funny George Burns & Gracie Allen broadcast from March 7, 1944) on Burns & Allen and Friends, and an adaptation of “The Glass Key” from The Lady Esther Screen Guild Theatre (07/22/46), which you’ll find on Smithsonian Legendary Performers: Dashiell Hammett. Happy birthday, Alan!